Parallel reasoning questions suck. I won’t dispute that. However, they are beatable. I’m going to teach you how to make peace with them and even benefit from solving these bad boys.

Some common advice for those who have trouble finishing the LR section on time is to skip parallel reasoning questions. That’s fine advice. They are typically among the more time-consuming questions, so skipping them frees up time to get easier points elsewhere. You can always come back to them at the end if you have extra time (do not, however, forget to mark a guess answer on your first pass).

Because they plan to skip them, some prep students choose to stop practicing PR questions entirely. That’s a big mistake. Parallel reasoning questions are terrific practice for honing your understanding of arguments. Even if you are using the skip and come back strategy, you should attempt to master these questions. Always do them before you look at the answers to a section.

Here, we help you figure out how to crush them. You may find that you get your skill level to the point where you feel comfortable attacking them right away on your practice tests.

Now, a couple of the prep companies give pretty harmful advice for dealing with these (I’m looking at you, Kaplan and PR). They give a “short-cut” approach, which compares the conclusions and eliminates those that aren’t similar. While that often can eliminate two or three answer choices, we want you to be able to solve the damn problem!

To do that, it helps to have a firm foundation in conditional reasoning. If you are shaky, check out our FREE conditional reasoning lesson. However, parallel reasoning questions don’t test your ability to grapple with the logic in an argument. Rather, they test your ability to spot the overall structure of the argument.

Basically, that means that you aren’t making inferences. Rather, you are just trying to find another argument that contains the same structure as the stimulus. That’s why these are so time-consuming — you have to analyze the structure of the stimulus, then compare it with the structure of all five of the answer choices.

Going Block By Block: The Anatomy of A Parallel Reasoning Question

Let’s talk about this abstractly for a moment —

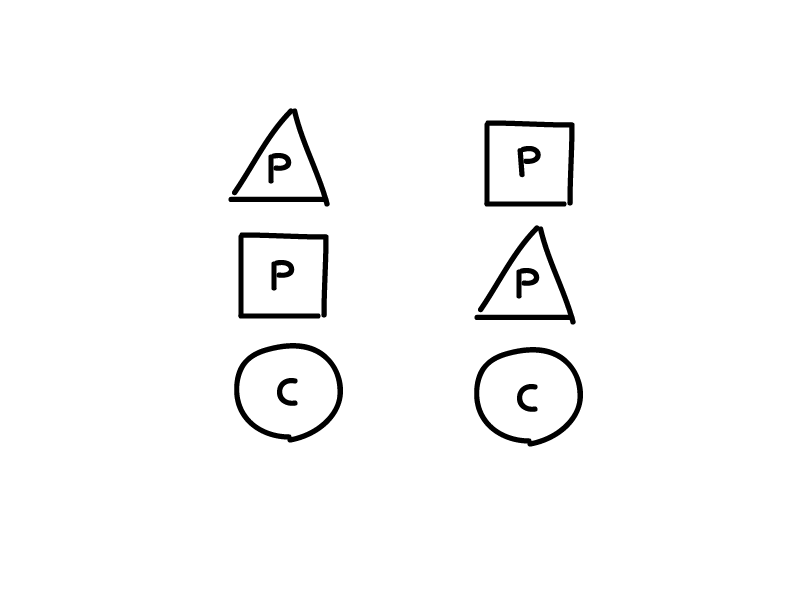

I want you to think of arguments as a little group of blocks. Each block is one piece of the argument. A pretty typical argument on the LSAT will contain a couple of premises and a conclusion. That’s three separate blocks.

Now, these blocks come in different shapes. What you need to do is find an answer that has the same blocks as the stimulus. That means that both arguments have the same number of blocks, and they match in size and shape.

Now, forget the content. Topic does not matter AT ALL when comparing arguments on a parallel reasoning question. The stimulus can be about lions, and the correct answer can be about aliens. Content matters not. The form is what matters.

The order doesn’t matter either. The same blocks that you had in the stimulus can be all jumbled up in the correct answer. Let’s take a look at how this might look in the abstract:

Now, that gets us a small part of the way, but now we need to understand what makes a circle a circle and a square a square. For that, let’s look at an example. Note the following isn’t a real LSAT question, but it contains identical reasoning to the one you might encounter.

Parallel Reasoning Example

If Tom Brady is healthy, It would be highly unlikely the Colts will win their match-up with the Patriots. But in fact, it happened that the Colts did win the match-up, so it’s highly unlikely that Tom Brady was healthy.

The pattern of reasoning in the argument is most similar to that in which of the following arguments?

Okay, let’s pause here and take a look at our blocks.

Block 1:

What is the first one? If Tom Brady is healthy, It would be highly unlikely the Colts will win their match-up with the Patriots.

That’s a conditional statement. It’s kind of an A –> B. However, it’s also got this extra element of “unlikely.” You don’t know for a fact that B is going to happen, just that it’s very likely. Now, that is all we need to know about this block. That’s it. When we look at the answer choices, we will be searching for this same kind of block. Now for Block 2.

Block 2:

But in fact, it happened that the Colts did win the match-up, so It’s highly unlikely that Tom Brady was healthy. This is just saying, B didn’t happen; therefore, A is unlikely. It’s pretty much a contrapositive of Block 1 and also has this “unlikely” language.

Great, that’s a block. We need to find something just like this in the answer choice.

I’m going to simplify this with just two answer choices: A correct one and one that looks close but is not right.

Answer Choice A:

If the soccer tournament was not rigged, the team that won it would have been highly unlikely to win the whole thing. Thus, since this team was highly unlikely to win it, the tournament was probably rigged.

Answer Choice B:

If President Obama was a speaker at the event, it’s highly unlikely that Fox would cover the event. It’s very unlikely that Obama did speak since, as it turns out, Fox did cover the event.

Now let’s look at A. It’s got block 1 covered. This first sentence is a conditional statement, a typical A —> B, with this highly unlikely language (so B is not certain). That’s just like block 1. So far, this question is on the right track.

Now, I look at the second sentence. It’s got more of that unlikely language, so that sort of checks out and looks right. However, nowhere do we have anything that looks like “B happened.” For this to check out, we have to know that this team did indeed win the tournament. We aren’t told that, so this is a bogus block. It’s a different shape, and you have to eliminate this answer choice.

On to answer Choice B. We know it’s right now, but let’s look at why. If President Obama was a speaker at the event, it’s highly unlikely that Fox would cover the event. Bam! That’s definitely a perfect Block 1—same conditional statement with unlikely language.

It’s very unlikely that Obama did speak since, as it turns out, Fox did cover the event. The first thing I’m looking at here is whether the “B happened” element is present. Yes. Fox did cover the event. That is just like the second block when the Colts did win. The unlikely did, in fact, occur.

Now, we need to see the conclusion that it’s therefore unlikely A happened. Boom! It’s there. The argument is now saying it’s unlikely A happened (It’s very unlikely that Obama did speak). Note the block is flipped around, but it still makes the same block. REMEMBER, the order does not matter.

You could even chop block 2 up and still have a valid, correct answer. Let’s look at that.

Fox covered a recent event. If President Obama spoke at the event, it’s highly unlikely that Fox will cover the event. Therefore, It’s very unlikely that Obama did speak at said event.

Still perfectly parallel. Even if the pieces are lying all over the floor, if you can still assemble them into the needed blocks, you’ve got the right answer. It might help for you to think of block 2 as actually two separate blocks.

That said, don’t get too hung up on the block analogy. The point is that these pieces can move all over the place. The order doesn’t matter. However, if one of the pieces is not right, you can’t build the same blocks, and it’s not the right argument. That means it’s a wrong answer, and you can quickly eliminate it.

Comparing Individual Premises And Conclusion

Note that the Kaplan and Princeton Review method of comparing conclusions would have actually worked in our example. Your attack plan is to compare blocks one to one, including comparing the conclusions (that’s often the best place to start). In our example, it was pretty easy. A big element of our Block 2 conclusion, something unlikely actually happening, was just not there. What about when it’s a little more subtle?

Conclusions (and premises) have to match in terms of their level of specificity (also often called in logic, “degree” or “extent”). So if the conclusion in the stimulus says that something is “always” the case, you have to see that same “always” language or something very close in the conclusion of the correct answer choice.

Think about our example correct answer. What if it said:

If President Obama was a speaker at the event, it’s highly unlikely that Fox would cover the event. It’s likely that Obama did speak since, as it turns out, Fox did cover the event.

This suddenly has the wrong ring to it entirely (and, in fact, seems like flawed reasoning now) because “likely” doesn’t match up with “highly unlikely.”

Making one-to-one comparisons like this can help you identify when blocks aren’t in the right shape.

Diagraming Parallel Reasoning?

You can do easier parallel reasoning questions in your head a lot of the time. Still, it would be best if you did not hesitate to rely on diagramming, especially for questions that use conditional reasoning. Practice often, and you will develop a feel for when you can do it in your head and when it might help if you do some diagramming.

For example, on the above question example, which is a little harder than the average PR question, I would have definitely written some stuff down. Even though I think about them as blocks, I don’t bother to label them like that. I would probably have written something like:

TomB Healthy ——-> Colts Win (Highly unlikely)

Colt won, therefore TomB Healthy (Highly Unlikely)

However, sometimes I make it fully abstract since it doesn’t take much extra time:

A —-> B highly unlikely

B, therefore A highly unlikely.

Diagramming is always a little idiosyncratic. The important thing is that you understand the logical relationships expressed by the diagrams.

Getting Better

Now, you should be ready to approach these problems. Even if you skip them while taking a timed section, you should always do the PR questions afterward. You should not worry too much about whether they take a long time to solve. Even some very high-scoring test-takers skip these problems and only hit them at the end. Taking the pressure off and learning how to do them right will naturally build speed.

If you find you are doing them in about 2 minutes, which is about typical for a PR question, you might be able to start trying them on the first approach on your practice tests (rather than skipping them).

We haven’t discussed a lot of the finer detail on PR questions (including how to deal with flawed reasoning). The best lengthy discussion of parallel reasoning that I’ve seen is in the Powerscore™ Logical Reasoning Bible.

To really work out your parallel reasoning skills, read the chapter on parallel reasoning in there, then hit the Powerscore™ Logical Reasoning Workbook. This gives you plenty of real LSAT LR questions of each type to practice on, along with explanations that apply the correct techniques to the problems. That’s not just for PR and PR flaw questions, either. It tests all the various logical reasoning skills that you learn in the LR bible.

Good luck, and let us know in the comments if you are having trouble with any specific parallel reasoning question. I have access to every LSAT question, and I’m happy to explain one if it has you stumped. Just say the PT, section, and question number, and I’ll add the explanation to this post.

This lesson is excerpted from our Mastermind Study Group. If you want to join, here’s how it works. You self-study (cheap!), but we are there to guide you every step of the way with premium lessons and coaching. Access us through the private forum or during live office hours. Join HERE.

LSAT Logical Reasoning Lessons

7 Comments

I really wish I found this site during my prep when I was still in the States. I do feel as though I could have benefited more from learning with you guys.

It’s just unfortunate that I wasn’t able to troubleshoot my scores and problem areas as effectively until I got to a certain point. Being able to use key terms for specific issues finally got me to your site which has been immensely helpful.

I’m a Biology and Science Education major so I have some insight on teaching. Seriously well done on this article. Apt analogies and solid comparisons that helped me pinpoint the issues behind why I kept missing 30-50% of these consistently.

Keep up the good work!

I also enjoyed the “Why you suck at the Logical Reasoning Section” post and it paralleled my journey to a T

is there a way to diagram the problems with squares, triangles, or circles like that one example?

Hey there! Thanks for your help – I’ve enjoyed reading your posts and learning about your story.

In regards to this article, I’m unclear about how the “unlikely” aspect can be validly transferred from one clause to the other… do you have advice for this? Thanks so much!

If Tom Brady is healthy, It would be highly unlikely the Colts will win their match-up with the Patriots.

But in fact it happened that the Colts did win the match-up, so it’s highly unlikely that Tom Brady was healthy.

Hi 🙂 Thank you for posting this. Could you post an explanation for question # 13 from section 1 of test #29? This is a parallel reasoning question that has me so confused! Thanks so much

I saw on a post in July that y’all were giving people advice on what schools they could get into and what not and figured that maybe you could help me out a little bit too.

-I am a junior that will be going into senior year with a 3.66 gpa

-URM

-consistent upward grade trend since after freshman year

-real world experience comes from an internship with the DA when i was in high school (don’t know if that is relevant)

-I haven’t taken the LSAT yet, but have started very light studying

Aiming for top 20 (but, what would other good options be?). Ideally, I would love to go to Georgetown. What are my chances? What would I need to do?

also, i’ve already held two internships- unrelated to law, though.

I say anything around a 165 or will give you decent chances at T14 schools. 170 and you are in at most of them. Keep your GPA as high as possible and focus on that LSAT. Don’t study haphazardly (it sounds like you might be right now). Pick an intense study plan and stick to it.

The high school experience won’t help you too much (I might not even put it on your resume).

As far as good options outside the T14, there aren’t any if you are paying full price. That is why ideally you want to get t14 caliber numbers, so that you have the choice between a top school or a slightly lower ranked school with a big scholarship.