In case you didn’t notice, we are taking you through strategies for specific LSAT logical reasoning question types. We just covered ‘main point’

questions a few days ago. Today, we’ll talk about LSAT logical reasoning “weaken” questions, another one of the major question types you’ll encounter on the LSAT LR section. Out of the 50 or so LR questions you’ll do on an LSAT, weaken questions usually make up about 10% of the questions.

Think you are good at picking apart arguments? It’s time to prove it. Being good at the LSAT LR section means that you can see weak spots in arguments and understand how to exploit it.

First, let’s look at how to spot a weaken question.

Typical LSAT Weaken Question Prompts:

- “Which one of the following, if true, most weakens the argument?”

- “Which one of the following, if true, most seriously weakens the argument?”

- “Which one of the following, if true, most undermines the reasoning in the argument.”

- “Which one of the following, if true, casts the most doubt on the claim above.”

Okay, that’s easy. Just look for some language about weakening, attacking, undermining, damaging, etc. Now let’s talk about the structure of these bad boys.

The Structure of LSAT LR Weaken Questions

In a weaken question, just as with every other LR question, you will encounter a short stimulus passage. The passage author will be presenting an argument, pretending that it’s solid. On closer analysis, however, the conclusion may be susceptible to attack. You need to hurt it by finding an answer choice that kicks away some of the support or shows that the support is inadequate. To be more precise, let’s state that in more technical terms as well: To solve a weaken question, find an answer choice that shows that the argument’s conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow from its premises.

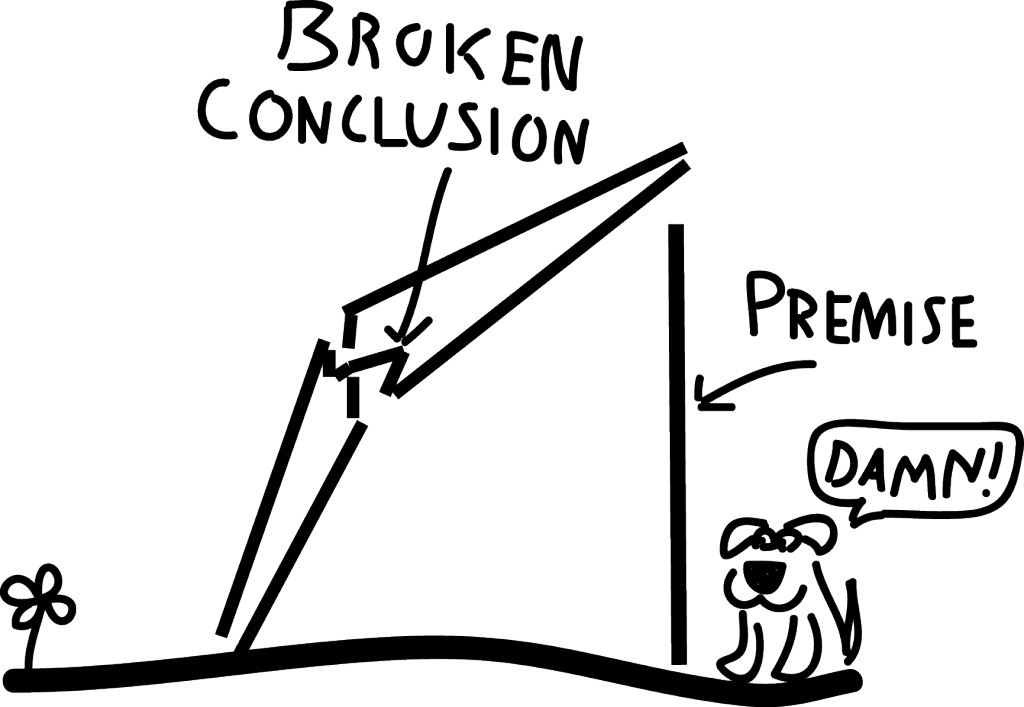

Let’s go back to our house metaphor from last time. Every argument has a conclusion support by premises. The premises hold up the conclusion like the walls of a house hold up a roof. Now, what happens when we kick away one of those walls? Bad things.

There are a couple of main ways to undermine houses (arguments). We’ll cover that later. For now, the essential concern is understanding argument structure. To solve weaken questions, you must be able to recognize when something is a premise, and when it is a conclusion. Unless you can distinguish premises from conclusions, you won’t know when an argument has been undermined.

Remember that the conclusion is the thing that gets support, whereas the premises are what gives support. I’ll explain that a little more here, but if you think you are solid on what’s a premise and what’s a conclusion, you can skip to the next section. If you need a refresher, consider the following argument:

According to our current understanding, life requires two things: liquid water, and an energy gradient. Europa, one of Jupiter’s moon, could conceivably support life. Tidal flexing creates thermal energy beneath the planet’s surface, melting ice into liquid water. Geological activity beneath the surface also provides chemicals that single-celled organisms could conceivably use for energy, forming the base of an ecosystem.

Now, what is what in this example argument? I picked kind of a technical argument to illustrate that you don’t even really need to think much about content to recognize the structure. This first sentence in the example (according to our current understanding, life requires…), is just providing background information. You’ll see extraneous information all the time on the LSAT. It’s not the main thing the author is trying to communicate and doesn’t directly support their position. Your common sense should help you filter out background information. Just focus on what the passage argues. Here, the argument is making a more specific argument about Europa, not making a broader argument that life requires two things.

Europa, one of Jupiter’s moon, could conceivably support life. This looks it our conclusion. This is what the author is trying to get across. How do you know absolutely that it is the conclusion? Because it gets support from the two premises that come after. Remember that the conclusion is what gets support and the premises are what gives it. This can be seen by asking yourself a question about the conclusion:

Why is there possibly life on Europa? Because there is liquid water and also a potential energy source.

Those who read the last LR post might remember this as the Why-Because test that we talked about there. It’s a great way to confirm what supports what, and thereby determine what a conclusion is and what are just premises. After a little practice you probably won’t have any trouble identifying conclusions and premises, but having a tool can help at the beginning.

Weaken Really Means Just Weaken

Okay, now that we know what our premises are and what our conclusions are, let’s discuss how to weaken them. I’ve used some pretty strong language so far (“kicking” an argument). However, I want to back away from that a little bit. The reality is that you are just looking for the answer choice that hurts the argument the most. You don’t even have to totally destroy the thing. Think of yourself as a saboteur in the middle ages (back when they had saboteurs). You have to sneak into the enemy castle, look for the weakest point, and then do the most damage you can. It doesn’t matter if you don’t ruin everything. Just doing the most you can is what makes you a good saboteur.

A good saboteur will often see the weak points right away. We always recommend you read the question stimulus first. When you spot a weakness in the argument, it will really help you pounce on an answer choice that exploits the weakness. That said, many times the logic in the argument is pretty sound looking. In those cases, and answer choice will often come along with a creative alternative explanation that casts doubt on the conclusion. What I’m trying to say is that this stuff is pretty subtle. If you are obsessed with the idea of “attack and destroy,” you might be overdoing it. Weaken questions call for finesse. You’ll see what I mean in the examples below.

The Many Two Ways To Weaken An LSAT Logical Reasoning Argument

The key thing you need to realize is that while there are tons and tons of facts that might weaken any specific argument, there are really only two basic forms that weakeners take. Let’s look at these, along with examples.

1) Attacking A Premise

If you knock out a premise, the support for the conclusion is now much weaker. Unfortunately, most correct answers on LSAT weaken question don’t touch the premises. It’s probably because something like this is straightforward and easy to spot. “Easy” and the LSAT just don’t mix.

Say you’ve got the example argument again:

Europa, one of Jupiter’s moon, could conceivably support life. Tidal flexing creates thermal energy beneath the planet’s surface, melting ice into liquid water. Geological activity beneath the surface also provides chemicals that single-celled organisms could conceivably use for energy, forming the base of an ecosystem.

Now I tell you “yeah, but the chemicals released by geological activity are heavy inorganic metals that don’t react with anything.” You are going to know that that argument is weaker, right? I just shot one of the premises all to hell. While rare, this may occur on a question, so watch out for it. Dead premise = weaker argument.

Conclusion Does Not Follow

This is a big one that the LSAT uses all the time. The answer choice will suggest that the same premises could lead to an alternate conclusion, casting doubt on the passage’s reasoning. Let’s look at this in action.

Politician 1:

Nicotine, the addictive substance contained in tobacco, is bad for you. Our Public-service campaign informing people of the dangers of nicotine addiction is clearly working well. Cigarettes sales have fallen 20% citywide since implementing the programs last year.

But now Politician 2 says:

Yes, but in that same time sale of e-cigarettes, another nicotine delivery device, and snus have increased five-fold.

It looks like people might still be addicted to nicotine. They just are picking different, arguably safer, arguably ways of doing it. Notice that for this to weaken the argument; it doesn’t have to obliterate it. It’s easy to imagine that the five-fold increase in other nicotine product sales does not in fact entirely explain the decreased cigarette sales. Maybe the campaigns are indeed working. However, politician 2’s statement casts significant doubt on it. Indeed, it makes it less clear that the conclusion (that the campaign is working) follows from the premise (cigarettes sales down).

A “conclusion does not follow” answer can also be thought of as leading towards an alternate conclusion. It’s like saying, “no, that conclusion isn’t likely bro. Here’s another one that is.” That conclusion, which goes unsaid, is that the campaign, in fact, isn’t working well (because people are still buying nicotine products, just different ones).

On a personal note, evidence suggests that e-cigarettes and snus (the Swedish stuff, not dip) are both much safer than cigarettes. If you are a smoker and can’t quit nicotine, definitely switch to one of those. But I digress.

Anyways, almost all weaken questions have answers that are of this “conclusion does not follow” type. Roughly, speaking, you are looking for an answer choice that blows the roof of the house, showing that these premises do not, in fact, support it.

Pay Attention To Specifics

A lot of people have big trouble with weaken questions, and the reason why is that they mercilessly punish people who don’t pay attention to specifics. The most common theme you’ll see is an answer choice that attacks a very similar conclusion to that in the passage, but not the right one.

Always, always, always make sure you know exactly what the conclusion said. You need to be zeroed in on the conclusion of the passage. You can’t attack the conclusion if you don’t know what it is and exactly what it says. Look at this example:

Fleckvieh Cattle are heir to a number of stomach abnormalities not present in the similar short-horned cattle. Farmers wishing to avoid the risk of costly surgical treatments would do well to select short-horned cattle instead, since short-horned cattle come from sturdy stock and rarely such incur extra costs.

Now you are choosing which answer choice that most weakens the argument, and you see:

(a) Fleckvieh cattle are much less costly to feed than short-horned cattle, which require a specialized diet.

A TON of people would pick that answer on the test. Their thinking is something like this: “this argument says that Fleckvieh cattle are more expensive, but this answer choice says that no, maybe they aren’t, which weakens the conclusion.” Without even seeing other answers, you can tell it’s a wrong answer. That’s because it doesn’t attack the specifics of the conclusion, which is about avoiding the risk of treatments. The conclusion said nothing about other costs or total costs, so you don’t weaken it by showing that Fleckvieh cattle might be less expensive in some other regard.

Pay attention to specifics, and you’ll start to find that weaken questions are pretty straightforward. If you don’t, they can feel like a dungeon full of traps. It’s your choice.

Honing Your LSAT Weaken Question Skills

Once you have a solid understanding of how weaken questions work, it’s time to start practicing them. I recommend a couple of things. First, learn how to destroy arguments on your own using the techniques above.

When you are still doing untimed questions early in your prep, try thinking about any fact that would break the connection between the premise and the conclusion. Do this before you get to the answer choices. Doing that will make it much easier to see an answer choice that also severs the connection. It will enable you to think like the makers of the test. Anytime you are doing that; you’re in pretty good shape.

Next, see how the masters think when solving these question. After, you’ve learned the techniques from here and from working in your Logical Reasoning Bible, then use the Powerscore™ Logical Reasoning Workbook. This book will give you a ton of weaken questions to practice on, along with explanations. Seeing the techniques applied to a lot of questions will reinforce proper mental habits.

Best of luck in your LSAT prep. For more tips and advice, sign up for our email list (we only send you our LSAT and law school articles, no marketing BS) or follow us on twitter @onlawschool

This lesson is excerpted from our Mastermind Study Group. If you want to join, here’s how it works. You self-study (cheap!), but we are there to guide you every step of the way with premium lessons and coaching. Access us through the private forum or in the live office hours. Join HERE.

LSAT Logical Reasoning Lessons

13 Comments

your article is so convincing that I never stop myself to say something about it. You’re doing a great job Man, Keep it up.

So what is the difference between a WEAKEN question that asks you to weaken an “argument” versus one that asks you to weaken the “reasoning?”

This is really clear and helpful!

Lots of typos though. 🙂

Thanks Alex. Point them out to me and I’ll hook you up with a $10 coupon for any product we offer!

In your last example, the conclusion is ” you should avoid Fleckvieh cattle if you want to avoid the risk of treatments.” So it is a conditional statement conclusion. Is the only way to have the conditional conclusion not followed would be one wants to avoid the risk of treatment, but can not avoid Fleckvieh cattle??

Btw, I like your website!

Thanks, Brandon.

Not sure what you are asking here but I edited for clarity a little.

Hi Evan,

Here is the example you provided:

Look at this example:

Fleckvieh Cattle are heir to a number of stomach abnormalities not present in the similar short-horned cattle. Farmers wishing to avoid the risk of costly surgical treatments would do well to select short-horned cattle instead, since short-horned cattle come from sturdy stock and rarely such incur extra costs.

I just want to ask if the following is the conclusion of this example:

Farmers wishing to avoid the risk of costly surgical treatments would do well to select short-horned cattle instead.

Thanks,

Brandon

Yes, that is the conclusion. Kind of a wishy-washy one but you’ll see that on the LSAT sometimes.

I believe the conclusion of your example should be

“Europa, one of Jupiter’s moon, could conceivably support life.”

Not “Tidal flexing creates thermal energy beneath the planet’s surface, melting ice into liquid water.”

Lol yeah. Sorry for the confusion anyone who read this before the fix. I guess I was copying and pasting too fast. Good spot Brandon. Hopefully it was clear that I was discussing the correct conclusion.

Hello LawSchooli:

I have been replying to the “Joshua” emails, are they even looked at? Nothing important, if you see reply’s, just delete ’em!

Thanks so much, cheers,

Sha.

Sha, we can be pretty bad at looking at those emails. Josh is pulling 80 hour work weeks right now. The fastest way to get us is usually on the comments. I always see those right away!

No worries, Evan. I am jealous of Josh! Pls, well, at some point if it suits the realm of discussion, pls point out, his “LSAT Conditional Reasoning” (July 22, ’13) explanation is appreciated!

Best,

Sha.