People knock on trial and error as a strategy for attacking a logic games questions and generally, yes, it’s a last-ditch option. However, it’s happens: you get to a question and your saying “wtf, I have no idea how to do this!” and trial and error is your only remaining option. In this post, we discuss how to use trial and error correctly so you don’t get stuck or waste too much time on really tough questions.

Now, the LSAT game questions are usually designed so you don’t have to resort to trial and error if, and that’s a big if, you see all the inferences. If you are a 180 every time LSAT taker, you might almost always quickly make the inference that leads you to the right answer. However, 99.9% of us aren’t 180 test takers. We miss inferences, and we don’t have unlimited time to sit around trying to make them — there are questions to be answered! When you miss an inference, situations come up where you want might want to use trial and error. What’s more, it seems to me the LSAT is increasingly introducing problems where almost all test takers will have to resort to trial and error. I can think of at least two such questions on preptest 69 (June 2013) for example.

The most common thing that leads to a trial and error situation is that you miss an inference while making your main diagram. This usually becomes apparent when you are doing global questions, questions that don’t give you any additional rules or restrictions. Let’s look at an example:

TRIAL AND ERROR EXAMPLE

Say you have a basic linear game with 7 spots and 7 variables: L, M, S, T, R, G, and H

Your base is going to look like this:

__ __ __ __ __ __ __

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

and say you have four rules:

Rule 1: L > S > T

Rule 2: H must be placed before at least 4 other variables (I usually diagram this: H > AtL4)

Rule 3: G is right after M

Rule 4: R is 6th or 7th

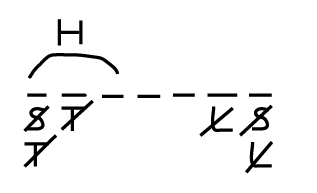

Now I start my main diagram that shows where things can and can’t go. Apologies for the bad drawing. My dreams of being an artist died early:

I’m ignoring rules 3 and 4 for now. In real life always get them all on there if you can, but they aren’t important right now.

Now I get to the questions and I see:

3. Which of the following variables CANNOT be third?

(A) S

(B) H

(C) M

(D) T

(E) L

What? This isn’t in my main diagram. The question is a global question, so I’m not getting any help from new rules. I think about it for 30 seconds but I still have no idea, and no strategy left except trial and error. So what do I do? Dig in and start trying them one by one trial and error style? Panic?

Don’t do either. The best strategy in this situation is to SKIP THE PROBLEM and come back at the end of the game.Tip: If you are stuck on a global LG question, skip it and come back. It’s almost always better than doing trial and error right off the bat.

Why do this?

1. You can use work on other questions to eliminate answer choices. If this is question 3, there could be up to five more questions that might help by showing that some of these variable can indeed go in position three. Any question can help just so long as it doesn’t suspend an existing rule.

2. You might make the inference later on. Usually, the LSAT only tests something once, therefore you won’t be messed up to bad if you hobble along without this inference. Meanwhile, you’ll have more time to work with the rules and might spot something later on.

3. Your understanding of the game will be better by the time you come back.

Use this strategy and you are likelier to finish more games on time and occasionally pick up a point along the way.

Coming Back To The Question

Now what happens when you get back to the question? I’ve read a lot of LSAT LG explanations and many of them show you the miracle inferences as if they just pop out of thin air. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always click like that under combat conditions. You got to scrap and use whatever you’ve got.

Hopefully, you’ve been able you eliminate one, two or more of the answer choices from work you’ve done on other questions. That’s great. You’ve already upped your shot of getting the question right by a lot even if you’ve gotten rid of two. Let’s say here that B and C got eliminated.

What else is happening? Well, by now you’ve done a lot of questions and the fact that H has to be in the first three has really sunk in. Look at the Q again:

3. Which of the following variables CANNOT be third?

(A) S

(B) H

(C) M

(D) T

(E) L

You hopefully think to yourself, “I think this question is going to somehow link up with the fact that H has to be in one of the first three spots. Some placement that makes that not possible might give me an answer.” That’s brilliant. More brilliant is realizing T has to have L and S in front of it, so if T is in the three spot, there’s no place for H. Boom! you solved it. (D) is the correct answer.

Now you can make inference that T can never be third just from looking at rule 1 and 2 back when you were making your main diagram. However, I’m thinking that more than 90% of the time a test taker is going to miss it in their main diagram. In fact, on questions like this, it’s likely the question was designed just so you will miss the inference in the main diagram.

Now if none of this magic happens and you never make the inference at all, you still aren’t in bad shape– You’ve got just three answer choices to do trial and error elimination with.

For answer choice A (S third) this works: LHSMGTR

Try answer choice D (T third) and you get LSTH… wait, we violated Rule 2. T can’t be third. That’s our answer. You only had to eliminate one answer choice before you got to the correct answer, and you saved big on time.

Putting It All Together

Even 170+ LSAT takers like Josh and myself use tactics like this all the time on practice tests. Being great at the LSAT isn’t about seeing all the answers easily. It’s about knowing how to handle anything you see. This strategy helps you scrap for points when things aren’t going perfect.

Now this tactic, like anything else, takes practice to get comfortable with. You’ll develop intuition for when you are going to be able make the inference and when it’s just not going to happen, in which case you should employ skip and come back strategy.

Use it and you’ll see that trial and error isn’t for dummies. When you do it right, it’s often the smartest thing you could have done.